5 - The concept of “Ludic” Reading

A key term that may be unfamiliar to readers of this study is ludic reading. The term was coined in 1964 by reading researcher W. Stephenson, from the Latin Ludos, meaning “I play”. A ludic reader is someone who reads for pleasure.

Many of the conclusions of this paper are reached as a result of examining the technology of the printed book in conjunction with research carried out by psychologists into reading, especially ludic reading. This is clearly the most relevant form of reading to the eBook.

Ludic reading is an extreme case of reading, in which the process becomes so automatic that readers can immerse themselves in it for hours, often ignoring alternative activities such as eating or sleeping (and even working).

A major shortcoming of most of the research carried out into readability over the last hundred or more years is that it has focused, for practical reasons, on short-duration reading tasks. Researchers have announced (with some pride) that they have used “long” reading tasks consisting of 800-word documents in their research.

Compare this with the average “ludic reading” session. Even at the low (for ludic readers) reading speed of 240 words per minute (wpm), a one-hour reading session – which in the context of the book classifies as a short read – the reader will read some 14400 words.

For very short-duration reading tasks, such as reading individual emails, readers are prepared to put up with poor display of text. They have learned to live with it for short periods. But the longer the read, the more even small faults in display, layout and rendering begin to irritate and distract from attention to content.

The consequence is that a task that should be automatic and unconscious begins to make demands on conscious cognitive processing. Reading becomes hard work. Cognitive capacity normally available exclusively for extracting meaning has to carry an additional load.

If we are trying to read a document on screen, and the computer is connected to a printer, the urge to push the “print” button becomes stronger in direct proportion to the length of the document and its complexity (the demands it makes on cognitive processing).

The massive growth in the use of the Internet over the past few years has actually led to an huge increase in the number of documents being printed, although these documents are delivered in electronic form which could be read without the additional step of printing. Why? Because reading on screen is too much like hard work. People use the Internet to find information – not to read it.

Research into ludic reading is especially valuable to the primary goal of this study, finding ways of making electronic books readable. If eBooks are to succeed, readers must be able to immerse themselves in reading for hours, in the same way as they do with a printed book.

For this to happen, reading on the screen needs to be as automatic and unconscious as reading from paper, which today it clearly is not.

If we can solve this extreme case, the same basic principles apply to any reading task.

5.1 - Ludic Reading research

“It seems incredible, the ease with which we sink through booksquite out of sight, pass clamorous pages into soundless dreams”

SW.H. Gass, 1972

Fiction and the figures of life

This passage is quoted in the introduction to “Lost In A Book”, written by Victor Nell, senior lecturer and head of the Health Psychology Unit at the University of South Africa.

Nell’s work is unusual and significant because it concentrates wholly on ludic reading, and details the findings of research projects carried out over a six-year period to examine the phenomenon of long-duration reading.

It looks at the social forces that have shaped reading, the component processes of ludic reading, and the changes in human consciousness that reading brings about. Nearly 300 subjects took part in the studies. In addition to lengthy interviews, subjects’ metabolisms were monitored during ludic reading. The data collected gives a remarkable insight into the reading process and its effect on the reader.

For anyone interested in reading research, this book is worth reading in its entirety. I’ll try to summarize the main points, then develop them. I’ve devoted a whole section to this book, because it’s such a goldmine of data.

Reading books seems to give a deeper pleasure than watching television or going to the theater. Reading is both a spectator and a participant activity, and ludic readers are by and large skilled readers who rapidly and effortlessly assimilate information from the printed page.

Nell gives a skeletal model of reading, then develops it during the course of the book.

Fig. 1: Nell’s preliminary model of Ludic Reading

Fig. 1: Nell’s preliminary model of Ludic Reading

5.2 - The requirements of Ludic Reading

Nell gives three preliminary requirements for Ludic reading: Reading Ability, Positive Expectations, and Correct Book Choice. In the absence of any one of these three, ludic reading is either not attempted or fails. If all three are present, and reading is more attractive than the available alternatives, reading begins and is continued as long as the reinforcements generated are strong enough to withstand the pull of alternative attractions.

Reinforcements include physiological changes in the reader mediated by the autonomic nervous system, such as alterations in heartbeat, muscle tension, respiration, electrical activity of the skin, and so on. Nell and his co-researchers carried out extensive monitoring experiments on subjects’ metabolic rates, and collected hard data showing metabolism changes in readers as they became involved in reading.

These events are by and large unconscious and feed back to consciousness as a general feeling of well-being. (my italics). This ties in well to how book typography has developed to make automatic and unconscious the word recognition aspect of the reading process, which we will examine later in this paper.

In the reading process itself, meaning is extracted from the symbols themselves and formed into inner experience. It is clear that the ability of the content to engage the reader (the “quality” of writing), the reader’s consciousness, social and cultural values and personal experiences all play a part in this process.

Nell says the “greatest mystery of reading” is its power to absorb the reader completely and effortlessly, and on occasion to change his or her state of consciousness through entrancement.

Humans can do many complex things two or more at a time, such as talking while driving a car. But one of these pairs of behaviors is highly automatized, so only the other makes demands on conscious attention.

However, it is impossible to carry on a conversation or do mental arithmetic while reading a book. The more effortful the reading task, the less we are able to resist distractions and the more mental capacity we have available for other tasks, such as listening to the birds in the trees or other forms of woolgathering.

One of the most striking characteristics of Ludic reading is that it is effortless; it holds our attention. The Ludic reader is relaxed and able to resist outside distractions, as if the work of concentration is done for him by the task.

The moment evaluative demands intrude, ludic reading becomes “work reading”.

5.3 - Highly-automated processes

Skilled reading is an amalgam of highly-automated processes: word recognition, syntactic parsing, and so on, that make no demands on conscious processing and the extraction of meaning from long continuous texts.

Although reading uses only a fraction of available processing capacity, it does use up all available conscious attention. Furthermore ludic reading, which makes no response demands of the reader, may entail some arousal, though little effort.

The term reading trance can be used to describe the extent to which the reader has become a “temporary citizen” of another world – has “gone away”.

“Attention holds me, but trance fills me, to varying degrees with the wonder and flavor of alternative worlds. Attention grips us and distracts us from our surroundings; but the otherness of reading experience, the wonder and thrill of the author’s creations (as much mine as his), are the domain of trance.”

“The ludic reader’s absorption may be seen as an extreme case of subjectively effortless arousal, which owes its effortlessness to the automatized nature of the skilled reader’s decoding activity; which is aroused because focused attention, like other kinds of alert consciousness, is possible only under the sway of inputs from the ascending reticular activating system of the brainstem; and which is absorbed because of the heavy demands comprehension processes appear to make of conscious attention.”

5.4 - Eye movement

Reading requires two kinds of eye movements: saccades, or rapid sweeps of the eye from one group to the next, and fixations, in which the gaze is focused on one word group.

Reading speeds vary. There is a neuromuscular limit of 800-900 words per minute. Intelligent readers cannot fully comprehend even easy material at speeds above 500-600wpm. The average college student reads at 280wpm, and superior college readers at 400-600wpm. Skilled readers read faster than passages can be read aloud to them.

Even skilled readers pick up information from at most eight or nine character spaces to the right of a fixation, and four to the left. Fixation duration is dependent on cognitive processing (i.e. is determined by the difficulty or complexity of the material being read).

Findings of a sophisticated study (Just and Carpenter, 1980) discredit the widely-held view that the saccades and fixations of good readers are of approximately equal length and duration, or that reading ability is improved by lengthening saccade span and shortening fixation duration.

Perceptually-based approaches to the improvement of reading speed (increasing fixation span, decreasing saccade frequency, learning regular eye movements, reading down the center of the page, and so forth) are unsupported by studies which, on the contrary, show skilled readers do not use these techniques.

Studies show all book readers also read newspapers and magazines, the converse does not apply.

Ludic readers read at wildly different rates, Nell’s study found the fastest read at five times the speed of the slowest.

The reading speed of each individual varied just as dramatically in the course of reading a book. One reader moved between a fastest speed of 2214wpm and 457wpm, while the average across the study group was a ratio of 2.69 between fastest and slowest speeds.

Nell found readers “savor” passages they enjoy most – often rereading them – while often skimming passages they enjoy less.

These last two findings suggest that any external attempt to present information at a pre-determined speed is doomed to failure, even if the reader is allowed to set presentation speed at their own average reading rate. The only method of controlling presentation rate which offers any hope of success would be to very accurately track the reader’s eye movements and link presentation rate to that.

Pace control is one of the reader’s “reward systems”, and terms such as savoring, bolting and their equivalents are accurate descriptions of how skilled readers read.

5.5 - Convention – or optimization?

“The appearance of books has changed very little in the five centuries since the invention of printing. Lettering has always been black on white, lines have always marched down the page between white margins in orderly left-and-right-justified form, and letterspacing has always been proportional”.

Nell refers to these and other typographic features as print conventions, which have exhibited extraordinary stability. Considered together with the unchanging nature of perception physiology, he says, they make Tinker’s Legibility of Print (1963) appear to be the last word on the subject, although many technological changes have caused legibility problems. For example, in many of these technologies, word and letter spacing is less tightly controlled; letters may be fractionally displaced to the left or right to create the illusion of a word space, thus compelling the reader’s eye to make an unnecessary regression. Poor letter definition and low contrast, distortion of letters and words are also cited as contributing to poor legibility.

Extraordinary stability is a key observation. It suggests that these are not merely print conventions, but optimizations that have stood the test of time. What worked, survived. What did not work disappeared. Survival did not happen because so-called conventions were easier for the printer (in fact, the reverse is the case), but because they are tuned to the way in which people read. Good typesetting requires much more work and attention to detail than bad typesetting. But bad typesetting is not acceptable to readers.

Nell describes these and other effects of the developing technology as “onslaughts on ease of reading”.

Ludic readers seek books which will “entrance” them; the reader’s assessment of a book’s trance potential is probably the most important single decision in relation to correct book choice, and the most important contributor to the reward systems that keep ludic reading going once it has begun.

Reader’s judgements of trance potential over-ride judgements of merit and difficulty. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (1954) is a relatively difficult book, but many readers prefer it to easier ones because of its great power to entrance. Best-sellers are entrancing to large numbers of readers.

Nell undertook a large and complex study of the physiology of reading trance using as his subjects a group of “reading addicts”.

5.6 - Reading and arousal

During reading, brain metabolism rises in the visual-association area, frontal eye fields, premotor cortex and in the classic speech centers of the left hemisphere.

Reading is a state of arousal of the system. Humans like to alternate arousal and relaxed states. Sexual intercourse is high arousal followed by postcoital relaxation; reading a book in bed before going to sleep uses the same arousal/relaxation mechanism – reading before falling asleep is especially prized by ludic readers.

This suggests an electronic book (eBook) had better be able to cope with being dropped off the bed! It also suggests that a backlit book, with no need to have a reading light - and perhaps keep a partner from falling asleep - is a positive benefit of the technology. Reaction to early backlit eBook prototypes confirms this is an attractive feature.

Ludic reading is substantially more activated than the baseline state. Immediately following reading, when the reader lays down the book and closes her eyes, there is a “precipitous decline” in arousal, which affects skeletal muscle, the emotion-sensitive respiratory system and also the autonomic nervous system.

Perversely, the ludic reader actually misperceives the arousal of reading as relaxation – they perceive effortlessness, although substantial physiological arousal is actually taking place.

During ludic reading, heart rate decreases slightly. This indicates that the cognitive processing demands made by ludic reading are not high. Reduced heart rate suggests that the brain is not working hard, which would demand increased blood supply, therefore increased heart rate.

This finding that reading involves arousal is highly significant; it suggests a strong parallel between the level of awareness we achieve while reading and the level of awareness required to survive in primitive times. In effect, we are taking an automatic skill developed for survival for a “walk in a neighborhood park”, during which we meet many old friends (words we know) and make some new ones.

Reading is a form of consciousness change. The state of consciousness of the ludic reader has clear similarities to hypnotic trance.

Both have three things in common: concentrated attention, imperviousness to distraction, and an altered sense of reality.

Consciousness change is eagerly sought after by humans, says Nell, and means of attaining it have been highly prized throughout history – whether through alcohol, mystic experiences, meditative states, or ludic reading. “Of these, ludic books may well be the most portable and most readily accessible means available to us of changing the content and quality of consciousness. It is also under our control at all times”.

There are two reading types: Type A, who read to dull consciousness (escapism) and Type B, who read to heighten it. Type A read for absorption, Type B for entrancement.

Automatized reading skills require no conscious attention. (This suggests that any distractions on the page which require the reader to make conscious effort (for example, poorly-defined word shapes, difficulty in following line breaks, etc.) will greatly detract from the experience.

Ludic readers report a concentration effort of near zero for ludic reading, climbing steeply through work reading (39 percent) to boring reading (67 percent)

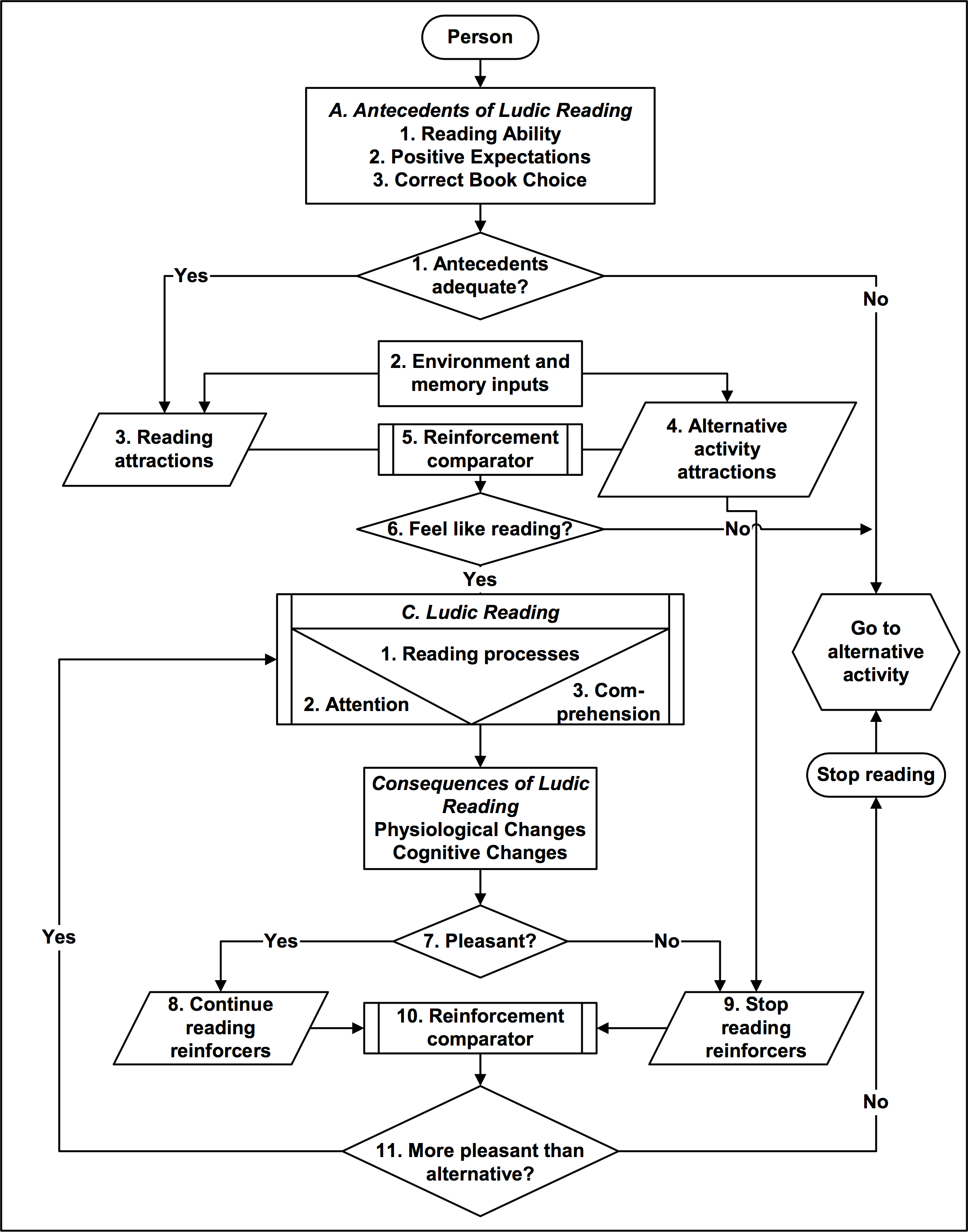

At the end of the book, Nell draws together the threads of his research to build a motivational model of reading, reproduced below.

Fig 2: Nell’s Motivational Model of Ludic Reading

Fig 2: Nell’s Motivational Model of Ludic Reading

5.7 - An expanded model

While this model sheds a great deal of light on the motivational aspect, it does not include a detailed examination of the “ludic reading process”, which is portrayed as a “black box”. For researchers who wish to examine the process itself in more detail, Nell cites the complex information processing model of reading developed by Eric Brown (Brown, E. R. (1981). A Theory of Reading. Journal of Communication Disorders)

Brown’s model, which takes up five separate pages, documents the true complexity of the reading process. Brown suggests that, contrary to previous theories that there are at least two different types of reading – phonemic and semantic – there is really only one, but that it is realized by fluent adult readers to a greater or lesser extent.

However, while an extremely complex sequence of events does take place in the reading process, it is normally automatic and involuntary.

Between Nell’s “black box” of the reading process, and Brown’s highly complex one, there is some middle ground which is worth exploring.

Expanding Nell’s “black box” only slightly gives a new, and I believe valuable, picture of the motivational model of reading.

There are at least three additional decision points that need to be added.

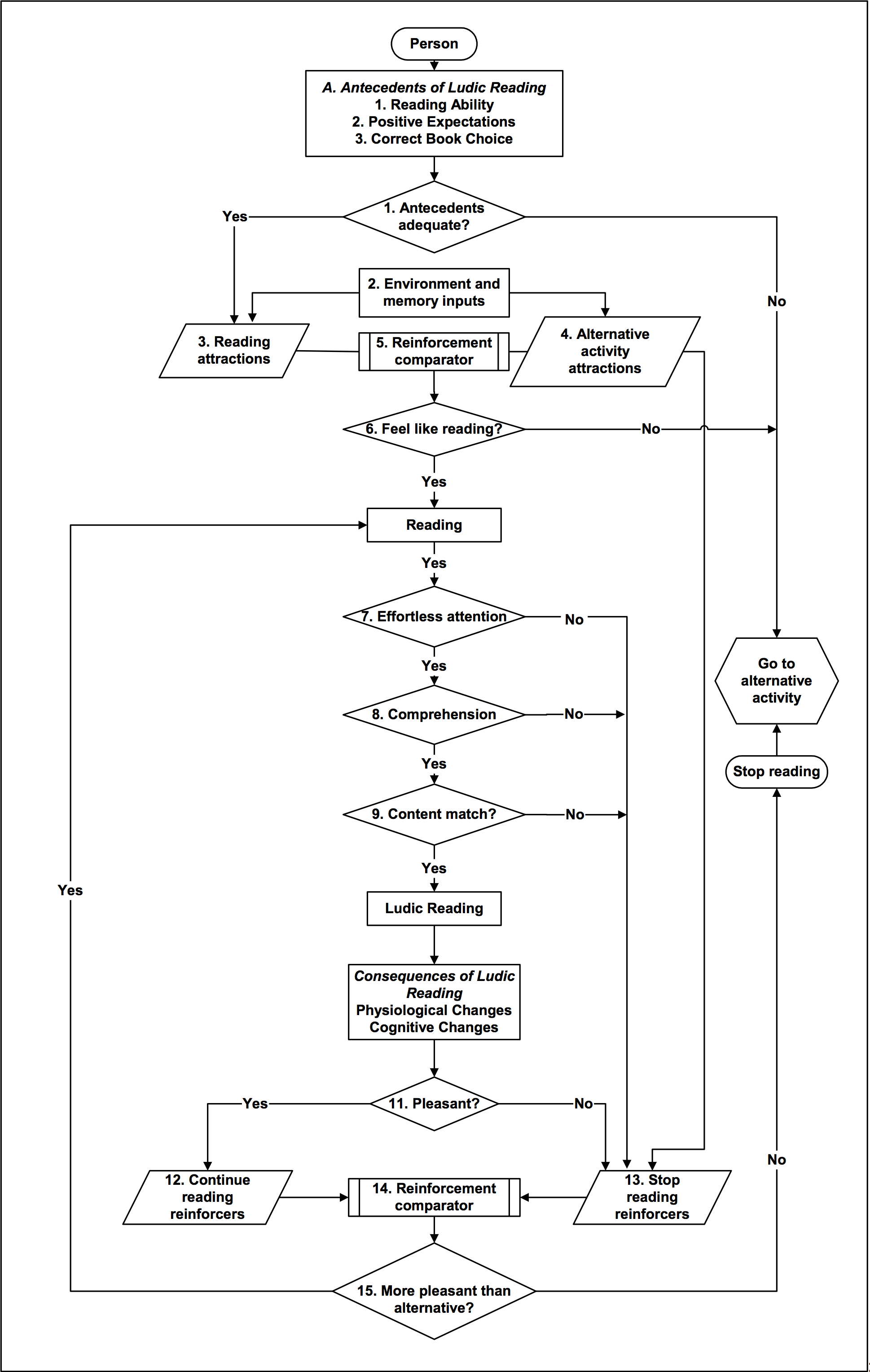

Fig 3: Motivational model with an expanded view of the reading process

Fig 3: Motivational model with an expanded view of the reading process

5.8 - Additional decision points

The three additional decision points consist of:

Degtree of Effort. The reader carries out continuous subjective evaluation of the effort she is expending to read the book or document. The key to ludic reading, as put forward by Nell, is that it requires subjectively effortless attention. The process is in fact a state of arousal of the system, not a state of relaxation. But the reader perceives that she is relaxed, and the perceived effortlessness of the task is a key to this subjective feeling of relaxation. Once reading starts to feel like hard work - reading a hard passage, reading material on which the reader will later have to answer questions, or straining to read poor typography – the perception of effort augments the “stop reading reinforcers”. Once perceived effort passes a certain threshold value, the reader will simply stop reading.

Comprehension. Evaluation is taking place continuously (Am I understanding this content?). The reader will certainly put in effort to comprehend difficult reading material (reading “broadens the mind”), but again there is a subjective threshold value. If it becomes too hard, reading will stop.

Content match. (Am I enjoying this book?) Nell’s model suggests this is a once-for-all decision covered by Correct Book Choice in the Antecedents of Ludic Reading element of his model, but in reality this evaluation must also be continuous, with a threshold value which if exceeded will also result in the reader ceasing to read. How many of us have started a book and failed to finish it because it did not engage us?

Electronic books have a level playing-field with printed books in relation to comprehension and content match, provided publishers and developers ensure the same kinds of content is available on screen as can be found today in any successful bookstore.

Best-selling novels and best-selling authors achieve their success because the level of comprehension and their content is matched to the comprehension and “absorption criteria” of the general book-reading population. When I buy an espionage novel by English novelist Anthony Price, I know before I begin that this author is able to consistently engage me with characters and plot. I have positive expectations based on his track record with me. I already “know” (have my own internal model) of many of the central characters. These are old friends, who make few demands on my cognitive capacity.

It is in the area of effortless attention that eBooks – and all electronic documents – face their biggest challenge. It’s harder to read on the screen today than it is to read print.

5.9 - Flow theory and the reading process

Nell’s analysis of ludic reading meshes extremely well with work on flow theory by researchers in recent years, the best-known of whom is Professor Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi of the Department of Psychology at the University of Chicago.

(For readers who, like me, have trouble with his name, it’s pronounced “chick-sent-mee-high”: I’m grateful to the magazine article that thoughtfully included the pronunciation, thereby removing a major obstacle from verbally quoting the author’s work…}

Csikszentmihalyi, in his US best-seller Flow: The psychology of optimal experience details how focused attention leads to changes in our state of consciousness.

Attention can be either focused, or diffused in desultory, random movements. Attention is also wasted when information that conflicts with an individual’s goals appears in consciousness.

What is the goal of the reader? To become immersed in the content. In this context, any information that takes conscious attention detracts from the reading experience. As Csikszentmihalyi says, “…it is impossible to enjoy a tennis game, a book, or a conversation unless attention is fully concentrated on the activity”.

He is even more specific later in his book, categorizing reading specifically as one of the activities capable of triggering the “flow state” by concentrating the attention.

“One of the most universal and distinctive features of optimal experience… is that people become so involved in what they are doing that the activity becomes spontaneous, almost automatic; they stop being aware of themselves as separate from the actions they are performing”.

He details activities designed to make the optimal experience easier to achieve: rock climbing, dancing, making music, sailing etc. In its most powerful form, the book, reading falls into that same category, as we will show later in this paper. The book is designed to capture human attention

5.10 - “On a roll”

Another researcher’s perspective on the flow experience appears in the paper A theory of productivity in the creative process (Brady, 1986), which examined how computer programmers achieve the state of maximum efficiency and creativity we call “being on a roll”.

The key to achieving the “roll state” is that concentration is not broken by distractions. “Interruptions from outside the flow of the problem at hand are particularly damaging … because of their unexpected nature”.

This data on the flow experience will resonate when we come to consider the psychology and physiology of reading and the typographic analysis in subsequent sections of this paper.