Callbacks

Callbacks aren't really a feature of JavaScript like Object or Array, but instead just a certain way to use functions. To understand why callbacks are useful you first have to learn about asynchronous (often shortened to async) programming. Asynchronous code by definition is code written in a way that is not synchronous. Synchronous code is easy to understand and write. Here is an example to illustrate:

var photo = download('http://foo-chan.com/images/sp.jpg')

uploadPhotoTweet(photo, '@maxogden')

This synchronous pseudo-code ⇗ downloads an adorable cat photo and then uploads the photo to twitter and tweets the photo at @maxogden. Pretty straightforward!

(Author's note: I @maxogden do happily accept random cat photo tweets)

This code is synchronous because in order for photo to get uploaded to the tweet, the photo download must be completed. This means that line 2 cannot run until the task on line 1 is totally finished. If we were to actually implement this pseudo-code we would want to make sure that download 'blocked' execution until the download was finished, meaning it would prevent any other JavaScript from being executed until it finished, and then when the download completes it would un-block the JavaScript execution and line 2 would execute.

Synchronous code is fine for things that happen fast, but it's horrible for things that require saving, loading, downloading or uploading. What if the server you're downloading the photo from is slow, or the internet connection you are using is slow, or the computer you are running the code on has too many youtube cat video tabs open and is running slowly? It means that it could potentially take minutes of waiting before line 2 gets around to running. Meanwhile, because all JavaScript on the page is being blocked from being run while the download is happening, the webpage would totally freeze up and become unresponsive until the download is done.

Blocking execution should be avoided at all costs, especially when doing so makes your program freeze up or become unresponsive. Let's assume the photo above takes one second to download. To illustrate how long one second is to a modern computer, here is a program that tests to see how many tasks JavaScript can process in one second.

function measureLoopSpeed() {

var count = 0

function addOne() { count = count + 1 }

// Date.now() returns a big number representing the number of

// milliseconds that have elapsed since Jan 01 1970

var now = Date.now()

// Loop until Date.now() is 1000 milliseconds (1 second) or more into

// the future from when we started looping. On each loop, call addOne

while (Date.now() - now < 1000) addOne()

// Finally it has been >= 1000ms, so let's print out our total count

console.log(count)

}

measureLoopSpeed()

Copy-paste the above code into your JavaScript console and after one second it should print out a number. On my computer I got 8527360, approximately 8.5 million. In one second JavaScript can call the addOne function 8.5 million times! So if you have synchronous code for downloading a photo, and the photo download takes one second, it means you are potentially preventing 8.5 million operations from happening while JavaScript execution is blocked.

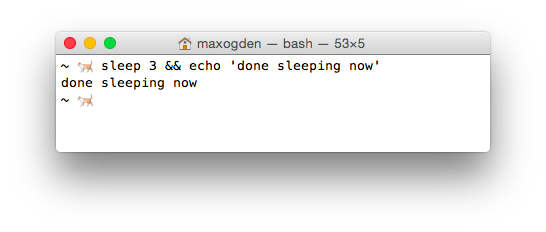

Some languages have a function called sleep that blocks execution for some number of seconds. For example here is some bash ⇗ code running in Terminal.app on Mac OS that uses sleep. When you run the command sleep 3 && echo 'done sleeping now' it blocks for 3 seconds before printing out done sleeping now.

JavaScript doesn't have a sleep function. Since you are a cat you are probably asking yourself, "Why am I learning a programming language that does not involve sleeping?". But stay with me. Instead of relying on sleep to wait for things to happen the design of JavaScript encourages use of functions instead. If you have to wait for task A to finish before doing task B, you put all of the code for task B into a function and you only call that function when A is done.

For example, this is blocking-style code:

a()

b()

And this is in a non-blocking style:

a(b)

In the non-blocking version b is a callback to a. In the blocking version a and b are both called/invoked (they both have () after them which executes the functions immediately). In the non-blocking version you will notice that only a gets invoked, and b is simply passed in to a as an argument.

In the blocking version, there is no explicit relationship between a and b. In the non-blocking version it becomes a's job to do what it needs to do and then call b when it is done. Using functions in this way is called callbacks because your callback function, in this case b, gets called later on when a is all done.

Here is a pseudocode implementation of what a might look like:

function a(done) {

download('https://pbs.twimg.com/media/B4DDWBrCEAA8u4O.jpg:large', function doneDownloading(error, png) {

// handle error if there was one

if (err) console.log('uh-oh!', error)

// call done when you are all done

done()

})

}

Think back to our non-blocking example, a(b), where we call a and pass in b as the first argument. In the function definition for a above the done argument is our b function that we pass in. This behaviour is something that is hard to wrap your head around at first. When you call a function, the arguments you pass in won't have the same variable names when they are in the function. In this case what we call b is called done inside the function. But b and done are just variable names that point to the same underlying function. Usually callback functions are labelled something like done or callback to make it clear that they are functions that should be called when the current function is done.

So, as long as a does its job and called b when it is done, both a and b get called in both the non-blocking and blocking versions. The difference is that in the non-blocking version we don't have to halt execution of JavaScript. In general non-blocking style is where you write every function so that it can return as soon as possible, without ever blocking.

To drive the point home even further: If a takes one second to complete, and you use the blocking version, it means you can only do one thing. If you use the non-blocking version (aka use callbacks) you can do literally millions of other things in that same second, which means you can finish your work millions of times faster and sleep the rest of the day.

Remember: programming is all about laziness and you should be the one sleeping, not your computer.

Hopefully you can see now that callbacks are just functions that call other functions after some asynchronous task. Common examples of asynchronous tasks are things like reading a photo, downloading a song, uploading a picture, talking to a database, waiting for a user to hit a key or click on someone, etc. Anything that takes time. JavaScript is really great at handling asynchronous tasks like these as long as you take the time to learn how to use callbacks and keep your JavaScript from being blocked.

The end!

This is just the beginning of your relationship with JavaScript! You can't learn it all at once, but you should find what works for you and try to learn all of the concepts here.

I'd recommend coming back again tomorrow and going through the entire thing again from the beginning! It might take a few times through before you get everything (programming is hard). Just try to avoid reading this page in any rooms that contain shiny objects . . . they can be incredibly distracting.

Got another topic you wanna see covered? Open an issue for it on github ⇗.